Building ShareChat's Audio Chatrooms | Mithun Madhusudan

How ShareChat built and scaled audio chatrooms to ~100m USD in GMV

Note 1: Long read littered with insights, so click the post title to read in your browser.

Note 2: It is only in late 2023/early 2024 that the monetisation potential of live audio has become more mainstream with companies like Astrotalk showing phenomenal growth, and others like Voice Club, FRND, and Clarity becoming part of the conversation. Micro transactions are the flavour of the day today, and a clear way to monetise India 2 users. This was not the case back in 2020. ShareChat audio chatrooms paved the path for this model. (scroll to the bottom for a tabular summary of current players in live audio.)

Note 2: This article is based on my experience building ShareChat audio chatrooms from mid-2020 to Oct 2021.

In the beginning, there was the pandemic

And with the pandemic came some massive behaviour shifts, especially in how people interacted online.

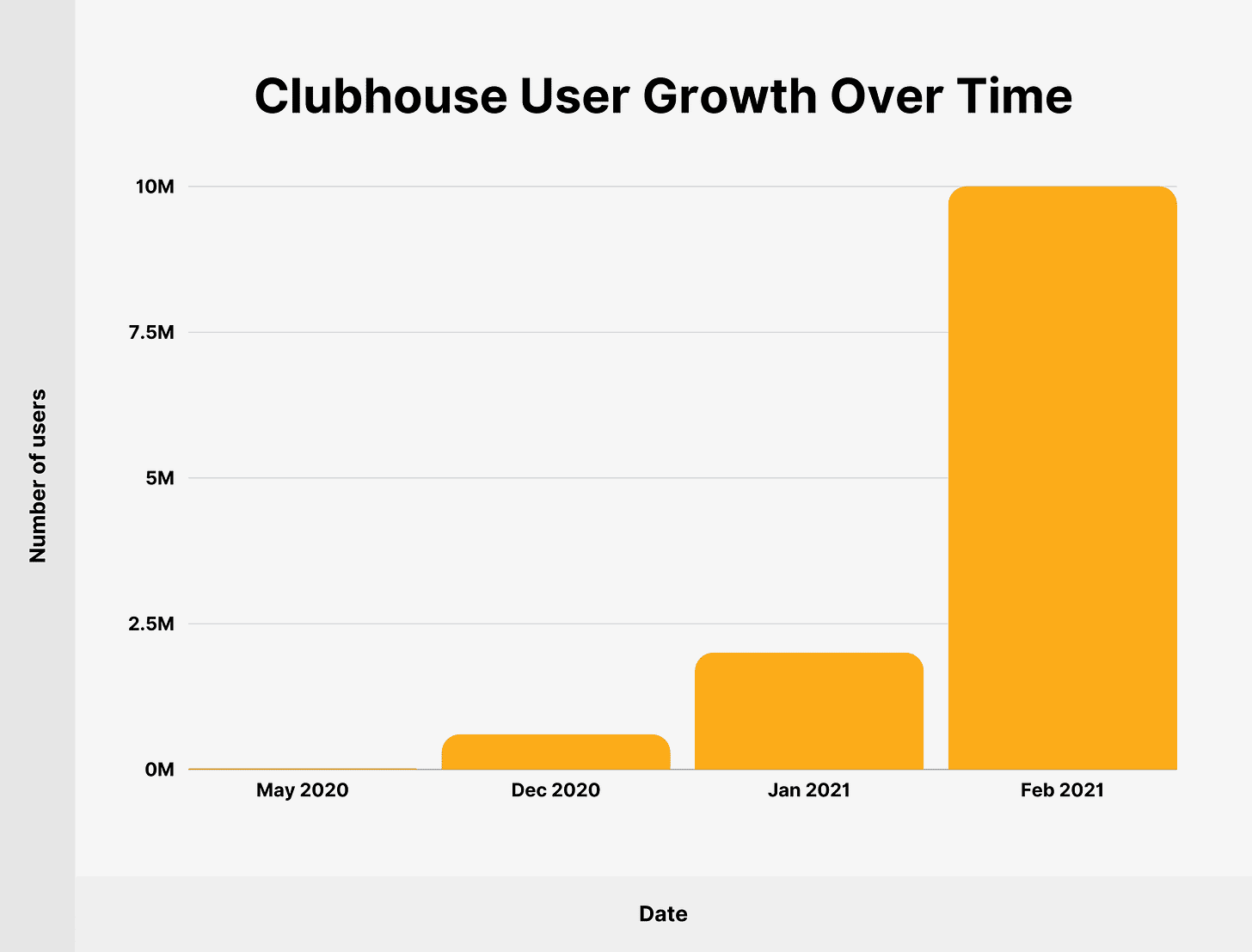

Humans are inherently social animals, and to plug the gap left by non existent offline interactions, a number of new forms of online interaction emerged. Of this Clubhouse was the one that is most well remembered, growing to millions of DAUs within a few months, and then fading into oblivion almost as fast.

Clubhouse was a very interesting product. Live audio rooms was a new format, and it was driving intense interest and engagement

At ShareChat we were watching this trend with interest.

As one of the largest social media apps in India, we knew our audience was looking for new ways to engage with each other. Although the primary product ShareChat offered was an AI generated home feed which gave users access to personalised content (text, images, videos), we had seen a lot of interesting sub cultures develop on ShareChat. One of these sub-cultures was ‘infinite comment threads’.

Underneath posts by female accounts, we would see our users (both male and female) initiate friendly conversations. Initially we dismissed these as standard social media behaviour (all social apps are eventually dating apps). But over time we realised that these comment threads were becoming communities of their own.

Users would bookmark the post where a conversation was initiated, and come back to it every day to continue in the replies. Almost all of these conversations were lightweight - the equivalent of ‘what’s up, what’s happening’ for our audience - and totally unrelated to the topic of the actual post.

This was super interesting for us, and led to a number of hypothesis on how we could capitalise on this behaviour of ‘meeting new people’. However, none of these gave us enough conviction to test out at scale.

Then the pandemic hit, and the macro conditions changed completely.

Because of the pandemic, the behaviour that was visible in comments was now a 10x larger need.

We also knew from competitor metrics that time spent on ‘live’ formats was orders of magnitude more than time spent on passive engagement (feed scroll). ShareChat's north star is engagement, which leads to retention, which leads to DAU. Our hypothesis for building a live product was ‘If live audio was adopted by a decent % of our audience, the time spent (proxy for engagement) of that cohort would grow, leading to an increase in retention.’

All of this seemed like the perfect setting for us to test out a new live audio product focused on connecting people.

What would such a product look like?

While we saw that Clubhouse was working (at the time), we were also aware that even though the live audio format might make sense, we would have to fundamentally repackage the experience for our audience - a young, non-English speaking user eager for relatable and accessible digital interactions.

Welcome to the Party!

If I had to summarise everything above as a mini PRD, this is what it would look like.

User Problem:

ShareChat users are stuck at home and want a way to interact with others and spend time in a digital world.

Potential Solution:

Live audio chatrooms is a novel format, where users can come together to participate in a live conversation. An easy way to visualise the solution is ‘Clubhouse’.

Live audio has the benefit of not requiring users to show their faces. This is important because the user is not confident about showing their faces on an app, and want to remain semi anonymous.

But, ShareChat is not a serious app, unlike Clubhouse. So we need to dress up the core live audio format and present it in a format that fits our audience. To do this, we need to define our audience a bit better.

Who is our audience? And what are his needs?

ShareChat’s user base skews young and young people would be interested in a live audio product (which is not as straightforward to interact with as a content feed).

The young user wants ‘fun’. There is enough non-fun stuff happening in his life and he wants an escape.

Anecdotally this young audience is also much more open to meeting new people.

A ‘party’ is something this audience is familiar with - as a slang for ‘having fun’. (‘Chal party karte hai!’)

Summary - The ShareChat audience is young and wants to party 🎉🕺🏽💃🏽.

Once we put all this together, our positioning started becoming clearer.

Audio chatrooms are a way for users to attend ‘happening’ parties digitally and meet new people.

A big benefit of articulating our positioning this way was that it gave us a central theme to craft the entire user experience around.

For example, the landing page mimicked what you see when you enter a party - a lot of small groups having different conversations. You can then browse through these conversations (individual chatrooms) to try and find something interesting.

Once you selected a conversation to be a part of, you could request the host to be part of the active set of people who could talk to each other (7 participants + the host), or stay as part of the audience listening to the conversation. (very similar to Clubhouse or Twitter Spaces).

PS: How to get accepted into these conversations is another interesting mechanic which we built on - more on that later.

For the actual room design, we looked at a lot of models, but eventually decided on the prevalent designs of similar apps on the Play Store. We ended up with something like this.

What we expected after launch was what PMs like to call ‘the happy flow’. Users find the product, they use the product, metrics go up and to the right, and we all live happily ever after.

So that’s obviously not what happened.

The Big Launch. And The Big Fail.

Anyone who has worked in consumer social knows that it is the hardest kind of product to build.

In general, consumers don’t give a shit about your app.

In consumer social, they given even less of a shit.

(A corollary is that consumer social is a tough place for PMs to be in, and I’ve always had a belief that the best consumer PMs are the ones who are willing to really really struggle to build products that work.)

We launched the first version of the audio chatrooms product fairly fast, going from concept to launch in ~6 weeks, working as a tight engineering, product, and design pod, and cutting out features which were absolutely unnecessary.

However we quickly we realised that the product was not working.

Live is concurrent. The product doesn’t work if there aren’t enough people in the room at the same time.

Hosts have to put in a lot of work to keep the conversation going and sustain this critical mass of users. Nobody likes boring parties.

But the hosts did not have clear incentives to ‘keep the party going’.

This meant we didn’t have enough active rooms at any point in time for the chatrooms product to make a large enough dent in the overall ShareChat context.

So we went back to the drawing board.

We looked at our initial thesis of making audio chatrooms a ‘place to join parties’ and tried to figure out what we were missing.

We re-articulated our test hypothesis, and went through each step by step.

If consumers are part of good parties, they will engage more.

Great parties need great hosts.

Hosts need an incentive to host these parties because live audio is high involvement.

Of these the most important hypothesis was (1). We tested this by seeding chatrooms run by our own internal ops team. Engagement was significantly higher in these, and gave us confidence that the product would work if there were enough good hosts .

But we couldn’t run chatrooms with internal hosts indefinitely. It was clear that we needed an incentive which would get good hosts to sign up and run great rooms on our platform.

The clearest incentive to get people to do anything is always money, and we had seen a lot of tipping (users paying hosts) models emerge in China where hosts were paid for conducting good live sessions. So this seemed the obvious way to proceed.

But who would pay and why? We couldn’t bankroll the hosts indefinitely, so the monetary incentive had to come from users.

Cue audible gasps - India 2 users paying? In a tipping model? To attend <gasp gasp> online parties. Surely you’re joking Mr. Mithun.

Now we were in super risky territory. Our active hypothesis was

Consumers will pay to be part of interesting parties.

On the face of it, this is the kind of hypothesis that your mother always told you to avoid. But good consumer products are built off of risky non-obvious hypothesis like these.

Looking back at our analogy of offline parties, we thought this was a fair assumption, but risky nonetheless. After all people did pay for access to good parties (in the form of cover charges).

But we still needed a stronger story to build our user experience around. Our hypothesis was that users would pay to join exciting chatrooms (parties). But we still needed to understand the ‘why’. Why would users pay? What is it about a party that makes people want to attend? What are the mechanics governing getting invited to a party and having fun? What makes parties ‘cool’?

So we went back to school.

Do you know why a lot of social products target teens as their early adopters? Because teenagers are more uninhibited in their display of core social mechanics.

For all the hopefulness of youth, teens are notorious for exhibiting behaviours which are considered less than kosher for adults. Inclusion, exclusion, sharing, social status - social mechanics which adults are a bit more subtle about, are overt and obvious in school. (hence the popular saying ‘kids can be really cruel’.)

(I can almost hear the painful school/college memories of being excluded coming back to haunt a lot of you, so apologies for that).

As a teen, you have an innate need to be cool. And attending the ‘hip’ parties in school is a way to signal that you are part of the cool crowd.

And what did you do to get invited?

Either you were already cool (where my sports bros at?)

OR

You became cool by bringing something valuable to the party. A good venue (parents aren’t home), the latest video game (Contra FTW), or some Breezers (hello fake id!).

In the second case, you became ‘cool’ by bringing something obviously valuable to the party, and you got invited.

What is an obvious signal of coolness in a digital party though? How do you showcase your status (coolness)?

Once again we quickly arrived at money.

People who have lots of money get ‘automatic’ status.

If we could build a way for consumers to show that they had a lot of money, that would become a way for them to signal status, and get invited to ‘interesting parties’ i.e. chatrooms.

This is where our story started to converge.

Hosts wanted money as a incentive to host and run great parties.

Only ‘cool’ people are invited to parties.

Having money to spend is one way of showing that you are ‘cool’.

We finally had something resembling a core loop.

Pivot. Pivot. Pivot.

The insight that users were keen to elevate their social status (become cool) led to our big pivot — the introduction of virtual gifting, allowing users to buy their way into the spotlight, and confirm their status. This monetised their desire to be seen in premium digital spaces.

We quickly built and tested a virtual gifting flow. Users could buy gifts in a chatroom, and gift them to the host. The more expensive your gifts, the higher your ‘coolness factor’, and the higher your chances of getting invited to be part of the top 7 seats to chat directly with the hosts (and other ‘cool’ people). All this was very obvious and in your face, no subtlety at all.

And voila it worked!

We quickly saw uptake from users who were keen to buy gifts and pay the best hosts if it meant they could show higher status and be part of the best conversations.

When a user gifted a host, a bunch of animations in the room made it obvious to everyone else who the guy with the money was (you can visualise this as the rich guy entering a party with his entourage, fancy clothes, obviously expensive sunglasses++). Hosts also quickly understood who the users with paying capacity (with some help from the product of course) were, and invited them to the conversation.

Higher status meant more invitations to the ‘cool’ parties, which led to even higher status by association with the cool parties. (Think of this as ‘hey do you know who I met at X’s party?’ ‘You were invited to that, no way!’)

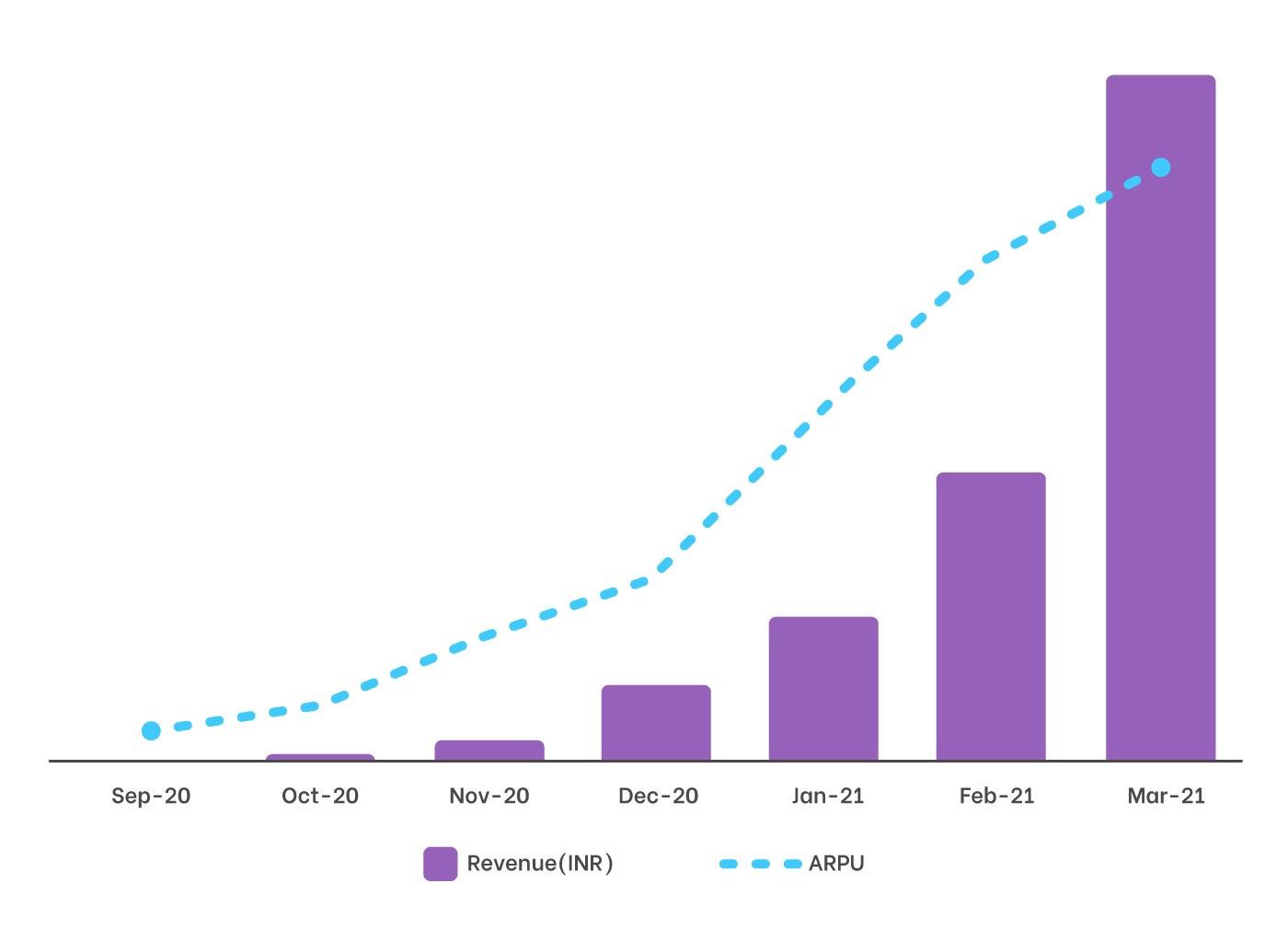

We had finally nailed our core loop and could see the magical ‘up and to the right curve’ that consumer PMs die for.

Establishing a Virtuous Cycle

The introduction of a virtual gifting system not only addressed the host engagement issue by incentivizing them financially but also tapped into the users' desire to showcase their status.

Even more importantly, this strategy catalyzed another virtuous cycle.

Hosts started getting paid, which attracted more hosts to the platform.

This meant there were more fun chatrooms for users to join.

Which meant there are more parties for users to by gifts in.

Which meant there was more gifting in chatrooms.

Which meant there was more money for hosts.

Which meant more hosts were attracted to the platform.

Ah the holy grail! A loop the kinds of which we had only seen in the decks of super successful companies.

Identifying Levers to Scale

Once this core loop started working, the job for us was to figure out how to make sure each part of the loop could be made better. This is what some companies get a growth team to do, but at ShareChat we never had a separate growth team - the product team owned growth.

Here are the levers we identified and built into our roadmap.

More hosts → We knew if we were able to add more hosts to the equation, the subsequent steps in the loop would get better. So we added ops processes to find high quality hosts, added a host referral program into our product roadmap, and iterated on host payout models.

More ways to show status → Users wanted to show status, so the obvious large set of features to build was ‘ways to show status’. This meant we added more expensive gifts, cooler animations, gifting leaderboards, and much more.

More ways to buy status → Once people are buying stuff on your platform, you can take the e-commerce analogy to get them to buy more. We added discounts, flash sales, bundling, and other affordability levers into our product roadmap.

A combination of this led the ShareChat audio rooms product doing 50m USD in annualised revenue by Oct ‘22.

Concluding Thoughts

What we did well.

The story that we wanted to tell ourselves about why this product work was very important. This led to a lot of useful analogies which we could test in product (like ‘getting invited to cool parties means you are high status’).

We iterated super fast. All consumer products at some level are hit and trial, and you have got to give yourself enough shots at goal to give yourself a chance of scoring.

We were not afraid of copying. Wherever we saw established mechanics, we straight up lifted them, and then tweaked them based on our learnings.

And last but not the least, we ignored the noise around not being able to monetise this audience. Sometimes you just have to make things work by sheer grit.

Over the last year, audio based micropayments have become mainstream - Astrotalk (astrology consultation), Voice Club (astrology, love++), Clarity (mental health), FRND (dating) are a few which are exploring the live audio route coupled with micro payments in specific verticals. This is a mechanic which works well for the India 2 audience, and has proven to monetise at a decent scale. It will be an interesting space to watch.

Reader Poll

Acknowledgements

The great team that worked with me during those heady days of 2020 - Nishad in Product, Akansh in Engineering, Chetan in Design (among other folks).

Sameer and Tejas who have scaled the audio product 10x over the last 2 years.

Ankush, Farid, Bhanu for their backing - never the kind not to take a big risk.

Further Reading

"The story that we wanted to tell ourselves about why this product work was very important. This led to a lot of useful analogies which we could test in product (like ‘getting invited to cool parties means you are high status’)."

This is a superb point. Many a times I have found myself less convinced of an idea and a clear indicator was that I did not have an exciting 'story' to narrate it (to myself or to others). Once there was a good story, it was easier to put in all I had got.